Thus far we have tried to clear away some of the difficulties which tend to impede an understanding of the Aposle Paul's letters; we have tried to examine what was his real aim and method; and we have taken a cursory glance at the whole group of his epistles. Now without further preliminaries, we can proceed with our specific subject, the Epistle to the Romans. I want to look at the epistle directly, and try to see it as a whole. I am sure that if we do this, we shall find in it not merely a series of more or less unrelated formulations some of which indeed are very dear and precious to us, but we shall find in it a definite structure which will give the epistle a new or heightened meaning as a whole, or even disclose some form of living organism, which can and will grow in us if we let it. I am convinced with Paul that the word is living seed and will bear fruit if we receive it into our being and nourish it there, instead of slicing it up for the microscopic investigating slides of our mind.

The problem that we have before us, you will appreciate more if, as I have suggested, you have ever tried to make an analysis of the Epistle to the Romans. That has been attempted many times, and the results are rather surprising, for when the usual method of rhetorical analysis is applied, the different parts of the epistle somehow do not seem to fit into each other or follow each other in what we recognize as logical sequence. I noticed recently in the American Friend, issue of December 4, 1930, a sermon on one of the verses of the epistles, preached by Alfred Joseph McCartney, in Washington, October 19, 1930; and he starts in this way:

"The letter of Paul to the Romans makes hard reading. It is quite a compliment to the intellectual and spiritual calibre of that group of Christians in Rome to whom the letter is addressed that they were expected to have the patience to read it through and to understand what it was all about. Have you ever attempted to read a substantial portion of it at a single sitting? The reader is likely to arrive at a state of mental exhaustion before he gets very far into the letter in his effort to hold on to the trend of the argument."

I think that pretty well expresses the popular attitude toward the Epistle to the Romans. A good many who at times seem to be rather fond of the Bible object to the Epistle to the Romans. They find it hard reading. They find it disjointed. I think this is1 not because the epistle is difficult or incoherent but because we are not thinking in the same tempo, we are not thinking on the same plane, we are not using the method of the Apostle Paul at all. We are trying to make this letter fit a pattern which Paul did not use, and of course we have trouble. We are simply trying to do what we used to do when we were in school and went to rhetoric class. Sometimes we had to analyze an essay. We found the introduction, the body of the essay and the conclusion and we reduced it to a more or less logical succession of ideas. Our trouble is that this letter is constructed in such a way that it is impossible to apply that method of analysis to it. It is conceived in simultaneity, not succession. Of course, when I say that the letter was not written in logical succession, I do not mean that it is not orderly. There is a higher order than logic.

You will remember that I said that Paul's letters were always "occasional," that is, they were not abstract or general treatises, like the so-called General Epistles for instance, but they were real letters written to meet some specific condition which had arisen. Thus in the case of the Epistle to the Galatians there was the problem of the Judaizers. In the case of the letter to the Romans, there is this difference. Here was no occasion forced upon the Apostle or adventitiously encountered by him, but he actually made the occasion. In view of the contemplated transfer of the scene of his actualizations, he took the occasion to sum up, as well as he could, his experience, his essential, or if you prefer it, his spiritual position. This was no dead thing to Paul, but a very living thing, life itself. He could no more dissect it and lay it out in neat laboratory order or intellectual sequence, than he could dissect himself. His aim was not to enable others to analyze his experience, but to present it as a live thing, and as vividly as possible, to the sole end that when others came in contact with it, they too might be urged to share in his experience, or rather, to experience it for themselves. It is for this reason that it cannot be made to conform to the ordinary rules of rhetorical analysis or literary composition.

I do not say that it is impossible for a trained mind to extract and segregate its intellectual content from the epistle, but when this is done we shall find that what is vital and characteristic in Paul's message has been omitted. The letter has not even a logical thesis as its subject. What Paul was trying to do was to stimulate people to live in Christ. He was not trying, as theologians say, to establish the thesis that the righteousness of God is revealed in Christ by faith apart from the law. Paul did put emphasis upon that thesis, but only because most of his readers were conditioned by their bringing up in the law, and he had to overcome that conditioning. But this was incidental to his real aim. To say that his efforts to meet conditions local in time and space constitute the substance of his message is to take the intellectual part for the living whole. It is to say that Paul has not written scripture, for the substance of scripture is eternal.

I have looked over many analyses of this letter but I have never seen a satisfactory one. For instance, I refer to C. T. Wood, Dean of Queen's College, Cambridge. His recent life of St. Paul shows a masterly command of all the most recent knowledge about Paul. He says that the doctrinal portions of the epistle are divided into three parts: (1) Justification; (2) Sanctification, and (3) Rejection by the Jews. This is no analysis at all if by an analysis we expect some indication of the structure of the epistle. Paul does not discuss justification in the first part of the epistle or in any other part. He scarcely uses the word. He does say that he has been justified, that is acquitted, which is one of the many pictures he gives of the change which has come over him, but to say that the epistle is a treatise on justification is entirely to miss its meaning. Wood gives no hint of the state in which Paul found himself and that is really the beginning of Paul's experience. I wonder under which head he would place Paul's cry, "Miserable man that I am, who will deliver me from the body of this death." And as for "Rejection by the Jews," that is no integral part of Paul's thought. The very problem to the mind of the modern man is, what possible relation can that conception have to the very real truth which Paul is obviously trying to impart.

Now let us turn to Richard Francis Weymouth, editor of "The Resultant Greek Testament" and author of the "New Testament in Modern Speech," a translation which I have found invaluable. He simply says that the heart of the gospel is Justification by Faith. That is a good formulation, particularly as it recognizes the fundamental unity of the epistle, but in no sense does it represent an analysis. It does not help us in making our way through the details of the epistle, and moreover he adds: "Justification by faith, mediated by the atoning death of Christ." Paul in fact never hints at the Atonement in this sense. But we shall come to that later.

One of the best-known authorities on Scripture at the present time is Benjamin W. Bacon, Professor of New Testament Exegesis in Yale Divinity School. He divides our epistle into two parts, a Doctrinal Section, and a Practical Section. The Doctrinal Section he analyzes as follows:

(1) God's conquest of Evil by Good in the Universe.

1. Justification

2. Sanctification

(2) God's working in Human History, The Choosing of Israel a Means of Redemption of all.

Here we have the same difficulty. Justification and Sanctification are emphasized again as structural parts of the epistle, although as subjects Paul does not discuss them at all. He does discuss Faith, but only in its functional aspects, not metaphysically. But what is worse, Bacon's analysis entirely divorces the so-called practical section from the essential structure of the essay. This I take to be misleading. There are not two parts, a doctrinal and a practical. It is all practical.

And so with any analysis we choose. Either it is so vague and general as to be meaningless, or if it constitutes in itself a real logically constructed outline, the chapters of the epistle as we read them simply will not follow the outline. There is evidently something out of the ordinary here.

Let us hark back to our rhetoric class again. You will remember that certain essays of Emerson, for instance, could not be analyzed in succession like other essays, but they were said to be cyclic in formation. That is, there was one central thought and the different portions of the essay did not depend on each other, but each one went back directly to that central thought, something like the spokes of [a] wheel, each going back to the hub but not immediately connected with each other. That, to my mind, shows that Emerson was nearer to the heart of his subject than the ordinary author; he did not trail off, so to speak, on a string of association but he was so full of his central thought that everything he said was vitalized by it and led back to it directly.

That gives an inkling, I think, of the way that this epistle of Paul's is constructed; only it is much more complicated, perhaps I had better say, living, than an essay of Emerson's. Emerson, after all, lived in his intellectual centre. He was a cold Brahmin, he lived on one plane, and his essays may well be described, or outlined, or analyzed on a single plane, whether cyclically or in succession. But it is not so with Paul. We have with him a three-dimensional thought. His letter is not a circle, it is rather sphere. At the core there is the heart of the subject, and from that heart proceed rays which are directly related to the heart, and not to each other. Therefore, if we grasp the letter as a whole and start from the heart and work outward, instead of working in succession, the letter has a perfectly lucid and beautifully consistent structure. But it is organic rather than logical.

I venture to use another similitude drawn from organic life. We refer to the peeling of an onion. The outer and less fundamental lines of thought in the epistle are represented by the outside layers. Then as we take off each layer, we get closer to the heart of Paul's thought, and finally reach that vital centre. Only we must remember that Paul did not work from the outside in as we do. He worked from the centre outward or better still, he saw the thing as a whole.

You must appreciate that the reason for this is that Paul is not thinking at all, as we use the word "thinking." His process of mentation is quite independent of any of the canons of rhetoric or literature. He is living, and is simply trying to picture his living. When any of us think we necessarily think by association. One thought follows the other. Our minds are so constructed that we cannot think in any other way. That is why ordinary writing has logical succession, and that is why we are disappointed when we do not find it in St. Paul. But when we come really to live, it is different. At those high moments we do not stop to think, we see the whole subject at once. We do not follow out the paths of a maze and reach our conclusion by association, but we look down on the whole subject and see all the paths at once, and we go directly to what we are after.

For instance, to use a very homely and, perhaps, silly illustration, if you see your mother attached by a dog, you do not reach the conclusion what to do by any logical sequence of thought; you do not think of the comparative value or worth of the dog and of your mother in the universe; you do not think of the possible danger to you; you do not think whether or not she might be able to defend herself without your aid, or perhaps better than if you interfered, but you jump right into the situation. All these considerations are, not in your mind, but in your being, at once.

And that was the way with St. Paul. He was not theologizing. He was not reasoning about proofs of God. He was not thinking out proofs of the existence of sin, as he called it, but something wrong in us. He was not thinking of any logical demonstration of the cure. But he was vividly alive to the fact of sin in himself. He was vividly alive to the fact that there had been given to him a way out. That is the heart of his doctrine, and the whole letter is dependent on just that fact of experience. The various chapters are merely expansions and illustrations of this central thought. They relate back directly to that central thought but only incidentally to each other. So if we start not with the printed beginning of the letter, but with the central thought, we find that there is a beautiful, organic structure.

|

|

|

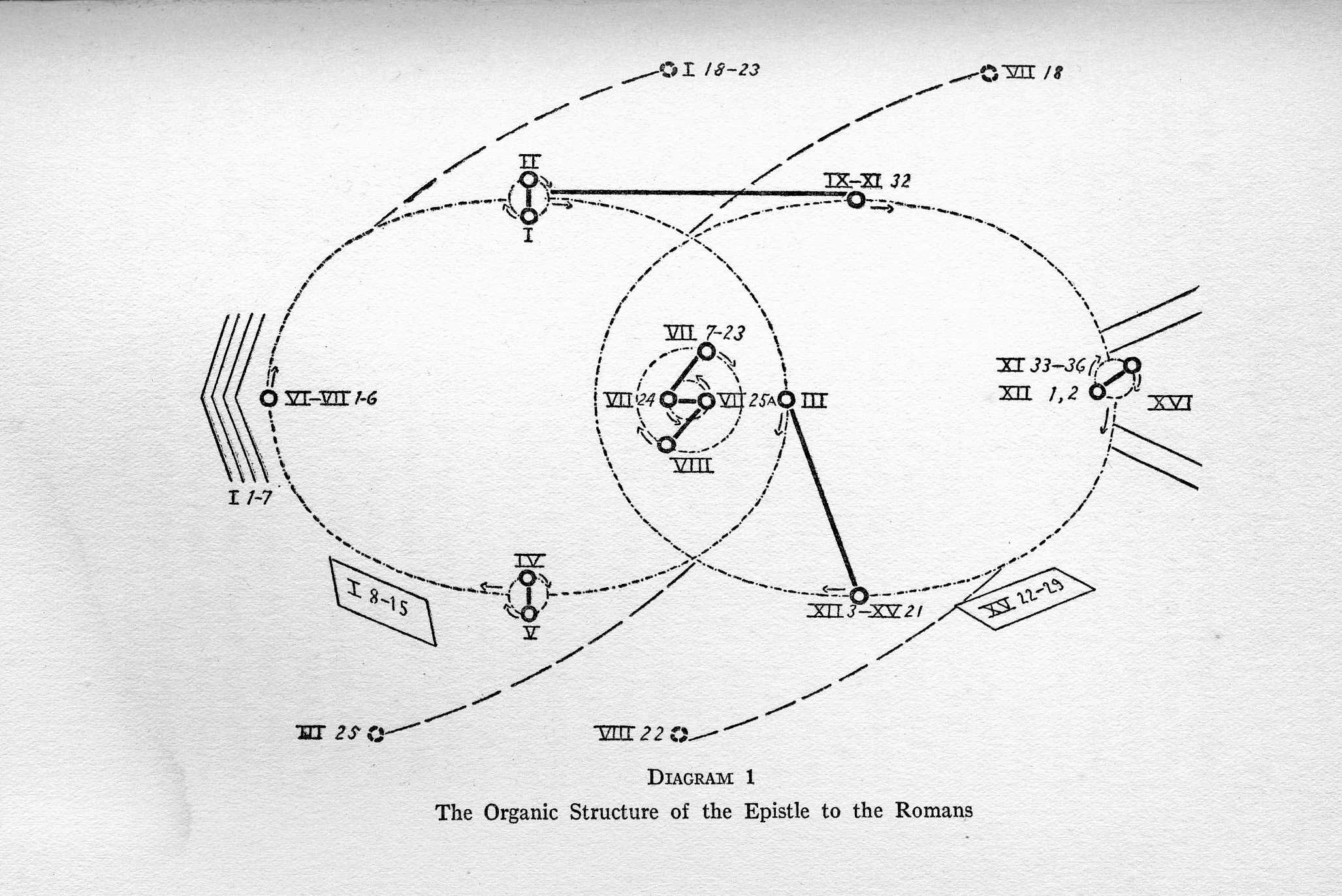

It is very hard to express this in words, and I do not know how it can be done adequately, for the subject matter is life not logic. But in making the attempt I want to use this diagram (diagram 1). Perhaps you will laugh at it, but at any rate, it will be a peg on which to hang my remarks. Somebody told me that it looks like an insect. I asked why, "Because those things look like antennae." I said, "Antennae don't grow out of the body, they grow out of the head." However, I am not entirely displeased if it looks something like an insect, because I feel that this epistle cannot be depicted only by somehing which is alive. Of couse I do not think that the diagram actually depicts the structure of the epistle, but I think at least that you will find it useful as an aid in following my words, just as I found it useful.

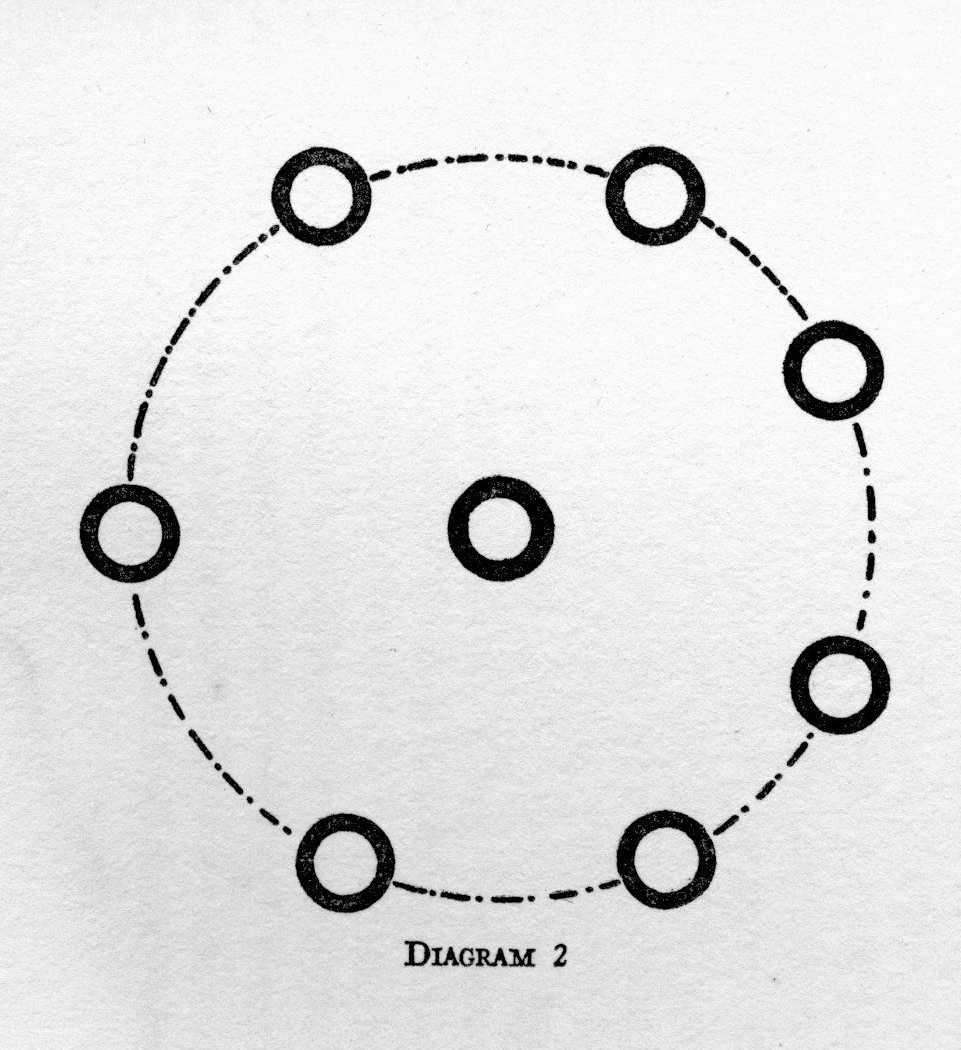

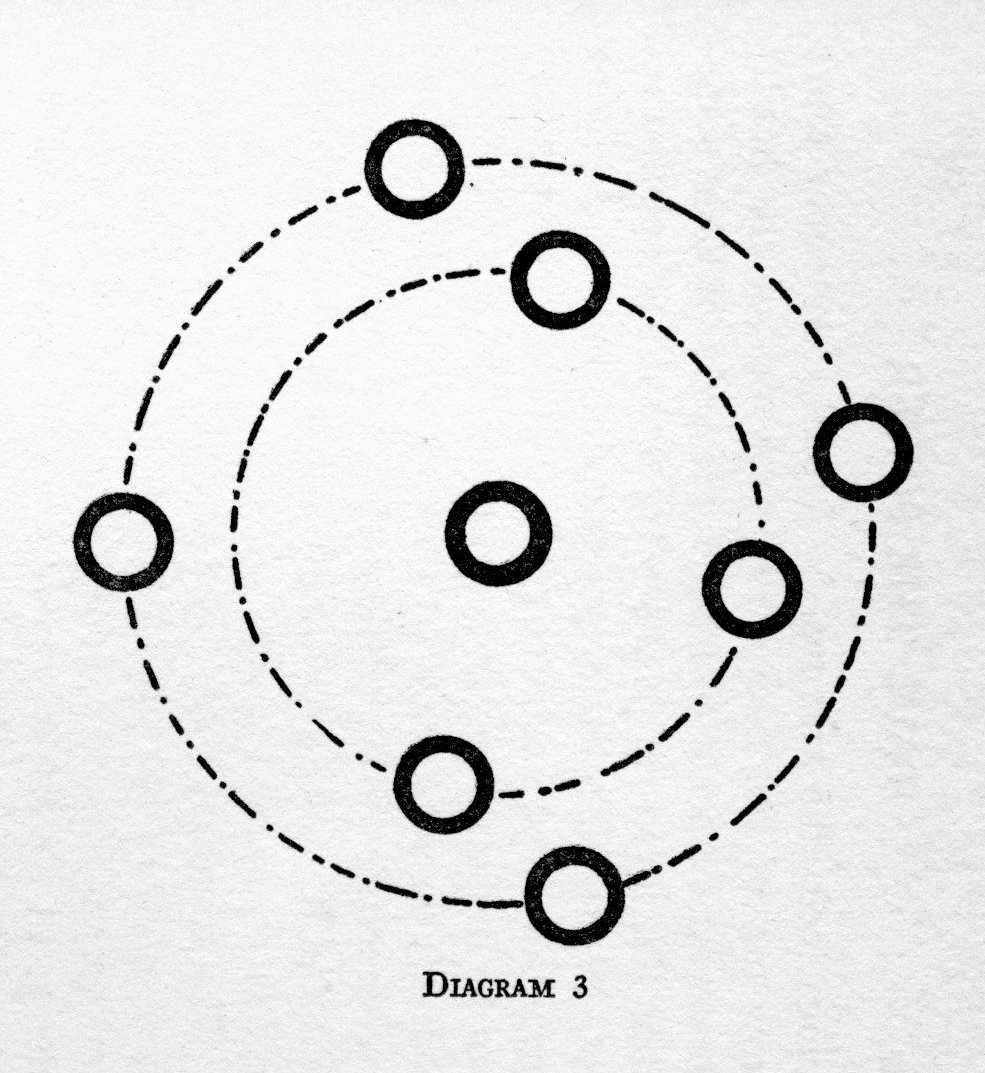

This diagram is based on one of the current conceptions of the structure of an atom. According to this conception an atom consists of a proton, a positive charge of electricity, around which revolve a number of electrons, negative charges of electricity, somewhat as planets revolve around the sun. The proton is the sun, the electrons are the planets. The electrons may be conceived in one orbit as in digaram 2. Or they may be conceived as grouped into two orbits, as in diagram 3. This represents in a rough way the structure of the epistle to the Romans. I have used a proton and two orbits of electrons rather than one orbit, because the epistle naturally divides itself into three parts, addressed severally to our three centres or foci of attention.

|

|

|

The heart of the epistle, where Paul lived, is of course the emotional or feeling centre. This is the proton. For the heart of the epistle, the proton, we have verses 24, 25 in the 7th Chapter:

"Miserable man that I am, who will rescue me from the body of this death? God, to whom be thanks through Jesus Christ our Lord."

Inconceivable as it may seem to us at first, the whole epistle is built on that double statement, the fact of sin and the way out. Everything in the epistle is in amplication or illustration of one-half or the other of that double statement, and relates back directly to it. The portion of the epistle before this proton is devoted more or less to intellectual demonstration, so I consider each of the first six chapters an electron and put them all into one orbit, say the inner orbit. The latter part of the epistle is addressed more or less to our practical nature, so the chapters which follow our proton I have grouped in the other orbit.

|

|

|

So we have our preliminary picture of the epistle, first of all a central sun, that double statement I have quoted. Around this sun revolve as planets the chapters of the first part of the epistle in one orbit, and the chapters of the last part in another orbit. Now if you will consider that these planets or electrons are held in the solar system or atom by their attraction to the central sun or proton and not by their relation to each other, you will begin to see how the epistle is really constructed, and why the ordinary method of logical analysis cannot be applied to it. Such method seeks for the essential structure in the relation of the chapters to each other. But in the case of the epistle to the Romans, the relationship of the chapters to each other is incidental not essential. Their essential relationship is to the central sn, the heart of the epistle.

The main difference between diagram 1 and diagram 3 is that I have pulled one orbit forward to indicate that it represents the earlier part of the epistle, and pushed the other orbit to the right to indicate that it represents the latter part of the epistle. This is the main change. I have made the orbits elliptical instead of circular merely for purposes of convenience, and there are some other details added which I shall refer to later.

Now let us look at diagram 1 more in detail. First let us look at the proton. This appears here in a form which requires some explanation. A living organism is not simple, and we are here dealing with a living thought. I have described the proton of an atom as a sort of central sun and so you might expect the nucleus of our diagram to be a single circle. But you will remember that some suns which seem to be one are really twin suns whirling about each other and functioning as a unit. So, as the statement which is the heart of our epistle is a double statement, the fact of sin and the way out, I have represented our proton as a twin sun, the two parts whirling about each other in a small orbit, the little circle at the centre of the diagram, representing in condensed form the two verses.

Immediately before and immediately after, Paul states more fully the thought, and so we have, as it were, as an addition to the proton, the 7th and 8th Chapters. In the 7th Chapter Paul relates in detail how he saw himself. He saw that he was not acting of his own will, but that something was making him act as he did. That was a great discovery, and explains what he means by "the body of this death." His other great discovery was the way out—only one way—and that is developed in Chapter 8, leading up to one of the greatest lyrical expressions of confidence and knowledge of the technique of Salvation (if we so wish to call it) which is found in any literature:

"Yet among all these things we are more than conquerers through Him who has loved us. For I am convinced that neither death, nor life, nor nature, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor any other created thing, shall be able to separate us from the love of God which is in Christ Jesus our Lord."

So in the diagram I have drawn a second circular orbit close to the first and on that second orbit I have put Chapters 7 and 8 as integral parts of our proton. So we have as our central sun not a twin sun but a sun in four parts. Disregard those four parts if it is simpler for you. Just consider that the heart of the epistle is Chapters 7 and 8, the double statement, the fact of sin and the way out. From that central thought the epistle develops itself. You must start from the centre and work outward in order to get the structure.

With chapter three Paul directs attention to the second half of the double statement which constitutes our proton, that is, Who shall deliver from sin? In chapter three he says that faith in Christ is the answer. In chapters four and five, which I have made a twin planet because of their relation to each other, he undertakes to demonstrate by illustrations from the Old Testament, the thesis of chapter three that faith is the way out of sin. We have observed how he and his hearers were conditioned by their upbringing2 upon the Old Testament. In chapter four he refers to the history of Abraham, and in chapter five to the history of Adam.

Now do not think that Paul in chapters four and five tried to prove from Abraham or from Adam the fact of sin or of faith. He simply used apt illustrations. Particularly the chapter on Adam has been objected to, where he says, "As in Adam all died, so in Christ all are made alive" etc.; the inference being that all his theology is based on what is at the present time considered to be a myth, and that the ridiculiousness (if we may say it) that we are all sinners because Adam sinned, leads to the thought of an equal illogicality, that if Christ was made alive we are saved by him. But you must remember that Paul, undoubtedly accepting the story of Adam, did not think that it proved anything to him; it was simply an illustration that appealed to his hearers as well as to himself. The proof of the pudding for Paul was this: He said, "I see in myself the war of the members." That was the point with Paul.

Further in regard to his use of the story of Adam. The other day I was reading over some of the Platonic dialogues, and I was quite struck with a passage in the Paedrus where Socrates had alluded to a Greek myth, and one of his followers said, "Why, you don't believe in a myth like that one, do you?" They were almost as modern in that time as we are. Socrates said, "Of course I accept the myths. I wouldn't take the trouble to disbelieve them. I have no leisure to investigate their truth at all: and the reason, my friend, is this: I am not yet able, as a Delphic inscription has it, to Know Myself. So it seems to me ridiculous when I do not know this, to investigate irrelevant things. Therefore, I dismiss these matters and accept the customary belief about them. As I was saying just now, I investigate not these things, but myself, to know whether I am a monster more complicated and more furious than3 Typhon, or a gentler and simpler creature to whom a divine and quiet light is given by nature."

That is the situation: whether it is better, as with Paul, to see himself, or to be able critically to distinguish between the historical and non-historical in the stories.

Reverting to the diagram, we have still to deal with chapter six, the last electron in the first orbit—the intellectual orbit. In that chapter Paul is approaching closer and closer to the heart of his doctrine. There he develops what faith is. He has said that what saves is faith in Christ; here he explains what faith in Christ is. It is not any form of belief or loyalty, but it is nothing less than dying with Christ, a process of voluntary suffering which must develop in us the action and attitude which Christ took. You may accept that or you may not; but that is undoubtedly Paul's message.

We have now finished the first orbit of electrons. The Epistle to the Romans is a long letter, and you may think that there are a great many words about two little phrases, for the whole letter is nothing but, "Oh, miserable man that I am, who shall deliver me? God!" That seems too small a nucleus for such an organism. But let us consider. If we go back to our Eddington, we find that such are the spaces—empty spaces we call them—in an atom that if the substance of a man were actually compressed so that there was left no intervening space, but only the substance of the protons and electrons, he would be so reduced that he could hardly be seen with a magnifying glass. Paul has been a little more considerate of us. We do not have to use a magnifying glass. We have only to open our eyes; not necessarily, though, only our optic organs.

Now let us speak about the last part of the epistle, which I have said is addressed to our practical or instinctive centre. This is represented by the orbit on the right [in diagram 1].

Chapters nine to eleven form the first electron. They are universalist in view-point. Paul says all shall be saved, even the Jews, just as he was saved. That portion of the epistle is, frankly, of secondary interest to us now, but it was of overwhelming importance to Paul because it dealt with what was really his own private problem, instinctive in him, on account of his conditioning. He loved his race, he was proud of his race, and he never could quite figure out logically how it was that, although the Messiah was to be given to them, when He came they rejected Him. I think, if we study the Epistle to the Philippians, we find that Paul eventually solved that problem. It was his undoubted thought, that if Christ had wished it, He would not have been rejected.

After this portion, which is a little difficult for us, and which is really a development of the second chapter, in which he states that the Jews have not righteousness, Paul reaches to a great height. I refer to the last portion of the eleventh chapter and the beginning of the twelfth. I think it is one of the most important parts of the Bible. I have represented it in the diagram as a twin electron or planet because the thought is twofold.

First Paul points out that it is impossible to have an intellectual conception of God:

"Who has known the mind of the Lord, or shared his counsels?"

He gives that up as hopeless. Then he points the way out:

"Present your bodies to him as a living sacrifice, which is your normal function. And do not be fashioned according to this world but be metamorphosed by the rebuilding of your mind so that you may learn by experience what God's will is."

Here we have the same insistence on experience, the same insistence upon the necessity of knowing our place in God's plan, the same insistence upon a complete metamorphosis which includes the complete dissociation from all our planetary predilections, a crucifixion to the world indeed. And all this is only our reasonable service, that is, our normal function. The Greek word is "logical," translated in I Peter 2:2 as "spiritual,"—spiritual milk. The Authorized Version says the milk of the Word. That is nearly it. If the Word represents true life, then the service of the Word is our normal service.

This tremendous statement serves as an introduction to what is called the practical section, which I have represented as another electron in the second orbit. Here Paul points out what happens when the logical function, has been appreciated and accepted and acted upon. This part of the epistle is sometimes made fun of. It is a list of rules of conduct, a gentleman's manual of behavior. But it cannot be dismissed so lightly. Paul well understood, and often says that adherence to these rules or any other means nothing at all. They are simply the fruit of the original giving up of self, the assuming of the cosmic duty. Furthermore this practical section is organically related to the sixth chapter where Paul points out what faith in Christ is, namely, dying with Christ. Dying with Christ is not a beautiful generality. This shows what it means in actual practical life. As a further indication of the importance of this section, we may note the 12th chapter, beginning at the 4th verse. While we are doing these things we are acting, not merely individually, but as parts of one body—one body in Christ, he says. We serve as organs for one another, and the success of the whole plan depends upon our co-operation.

Now we have finished with the main structure of the letter. There are some subordinate parts of the diagram that I ought to refer to and then I am through. Those other parts give the diagram the appearance not only of an atom, or of an insect, but of a dirigible also.

The lines on the left represent the introduction, the first seven verses of the epistle. They are most remarkable on account of what we have previously noticed, that is, that Paul saw the whole letter at once. He did not have to think it out. See what he put into those verses:

"Paul, a slave of Jesus Christ, called to be an apostle, set apart to proclaim God's gospel which He promised concerning His Son. By human descent he belonged to the family of David, but by his spirit of holiness he was miraculously marked out Son of God after the resurrection of the dead."

He sums up there, not only his authority and the substance of his gospel, but a disquisition on the person of Christ, and the nature of spiritual reality. The thoughts that are suggested here would take a lifetime to digest.

The tail of the dirigible is simply chapter sixteen, which includes personal remarks to various individuals.

Down below I have two "baskets," representing Paul's two statements of his intention to visit Rome, one in chapter one and the other in chapter fifteen. That there are two statements goes to show that the structure I have set forth is the actual structure. It is obvious that if the structure had been sequential, it would not have been necessary for balance to repeat these remarks, but as the thought here is three-dimensional, Paul found it advisable to put his statement on the two sides, just as we have two eyes and two ears.

There is another indication of this structure in the doxologies that are found in the Epistle to the Romans. We expect to find a doxology at the end of an epistle written in logical sequence, but here there are about six doxologies. In Ch. 16 verses 25–27, at the very end, we read:

"To God, the only wise, through Jesus Christ, even to him be the glory, through all the ages, Amen."

Ch, 15, verse 33:

"May the God of peace be with you, Amen."

The same chapter, verses 5 and 6:

"And may the God of patience and of comfort grant you full sympathy with one another after the example of Christ Jesus, that with oneness of heart and voice you may glorify the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Chris."

Ch. 11, verse 36:

"For all proceeds from him and exists by him and for him, to whom be the glory forever, Amen."

Ch. 8, verse 37–39, I have already read. It is a doxology in essence

You see what has happened. One doxology was not enough for Paul. He knew well enough that this was not a writing by the ordinary scheme of association with a beginning and an end, but a sphere the surface of which might be reached in many directions. Each time he came to the surface he had a doxology.

Now for these antennae, so-called. Some atoms are what is called radio-active. That is, they lose or expel some of their electrons from time to time. These radio-active substances are particularly valuable, vivid and precious. It seems to me that I see in this epistle certain elements evidencing radio-active properties, because they are not directly connected with the main thought, but interject, as it were, suggestions of profound ideas which do not simply scintillate but which glow with a light not of this planet, and which may be compared to the radiations cast off, for instance, by a substance like radium. There are many more, but perhaps these will suffice to give the diagram the proper radio-active appearance. Of course I shall not try to probe the meaning of these utterances. I am just trying to point out their existence.

The first I have chosen in Chapter 8, verse 22:

"For we know the whole of creation is groaning in the pangs of childbirth until this hour."

What is that childbirth? He says in verse 19:

"All creation is yearning, longing to see the manifestation of the sons of God."

It seems to me that the thought is this: The universe was created for the precise purpose of giving birth to beings conscious of their position and duty in the universe. These are the sons of God. It makes us perhaps feel our responsibility more if we ponder that thought.

Another is Chapter 7, verse 18:

"For I know that in me (i.e., in my lower self), nothing good has its home, for the wish to do right is there, but not the power. What I do is not the good I desire, but the evil deed I do not desire."

Paul came to that conclusion from experience. I think there are vey few who will admit frankly that they are acting, not as they will but as automata; and before you get a cure for the condition it is first necessary to recognize the situation. As Socrates said in the passage I have quoted, "Know thyself."

Chapter 3, verse 25: Here Paul says, referring to Jesus Christ,

"Whom God put forward as a mercy-seat through faith in his blood."

What does this mean? The Greek word which I have translated as "mercy-seat" is often translated as "propitiation," giving quite another meaning. Even Weymouth translates it "propitiation," but he excuses himself; he knows he is wrong. He says the Greek word is "mercy-seat," but that we can hardly use it because if we do Christ is made at once priest, victim and place of sacrifice. Weymouth has a good deal of understanding but in this case he does not seem to be able to think of the mercy-seat except as a place of sacrifice. The mercy-seat was the cover of the ark of the covenant and on the annual day of atonement it was sprinkled with the blood of the explatory victim. But it had a far deeper significance, and that is what Paul refers to here. It was the place of the presence of God. "For I will appear in the cloud upon the mercy-seat." Lev.16:2. We must remember also that "faith in his blood" does not mean "belief in the efficacy of the shed blood," but a faith in God resulting from a relationship with Christ so close that it amounts to blood kinship. So what Paul means is that in our kinship to Christ we find God.

There is another thought. Christ is a mercy-seat because without him we could never escape from our original state of slavery. I think of the doctrine of William Blake, where he speaks of what he calls the mundane shell as the "limit of contraction." From the sun the radiations of the divine love have gone forth, and they might go on to annihilation if it were not for the mercy-seat of God, this "limit of contraction," just this material world, where if we will we can begin to grow towards God. In the same way, he says, "Time is the mercy of Eternity." That is, out of the awful immensity of eternity, with which we cannot hope to cope, these moments are given to us wherein we may work out our own development.

So Paul too says Christ is a mercy-seat, not a propitiation: Living "in Christ," as he says, we look at ourselves impartially, determine what is wrong, and start on the road to recovery.

The other passage I have marked is Chapter 1, verses 18–23, a passage to which I have already referred a number of times. There Paul points out that in each one of us is full knowledge:

"God, before the creation of the world, gave to every man full knowledge of himself."

If we are ignorant, it is only because we have not troubled to pierce through the accretions with which we have been overlaid.

Of course you will understand that this diagram which we have been considering does not actually represent Paul's thought. For one thing the diagram is a plane, two-dimensional, while Paul's thought, viewed as an organism, is three-dimensional. Therefore if we are even to approximate the structure of the thought, we must imagine the diagram as having a solid form with length, breadth, and thickness. It would then be a working model instead of a picture. The nucleus is the throbbing heart. The orbits about it are not single line tracks, but living sheaths. The radiations are not like little projectiles, but are waves of consuming fire.

Even this would not be adequate correspondence; I don't think Paul can be pinned down in a diagram of any sort. I have used this diagram only as a means to an end, to give some sort of concreteness to my words. When we enter the life, as Paul entered into it, diagrams are meaningless; but at least this may be the sort of a figure that will show graphically that we cannot simply and easily say, "Oh, Paul is just using a lot of words without rhyme or meaning." There is a meaning; there is a structure. And to that extent the diagram is useful. It is not by chance that it takes the appearance of an atom or solar system. Every organism is a simulacrum of the universe. That is what being made in the image of God means. Our conception of the atom and the universe may change, is changing. But this does not mean that our diagram is false. It is true, relative to our present capacity of understanding.

I am reminded of Socrates again. In the Phaedo he had been explaining at some length about the soul and its future habitation, very definitely and concretely, almost as concretely and specifically as Swedenborg. When he had finished he said:

"Now it would not be fitting for a man of sense to maintain that all this is just as I have described it, but that this or something like it is true concerning our souls and our bodies, since the soul is shown to be immortal, I think we may properly and worthily venture to believe."

Then he says:

"For the venture is well worth while."

Paul wanted his readers to try an adventure in experience. We must not think that he was setting intellectual traps, trying to show his erudition, or putting his thought in a complicated form which would flatter the perspicacity of the Romans. He was doing what he did simply because he had to. There are some things in which we cannot follow our usual logical processes. I am going to refer once more to our Eddington. Speaking of spiritual activity, he says:

"There is a hiatus in reasoning, but it is hardly to be described as a rejection of reasoning. There is the same hiatus in reasoning about the physical world, if we go back far enough. We can only reason from data, and the ultimate data must be given to us by a non-reasoning process, a self-knowledge of that which is in our consciousness. To make a start, we must be aware of something, but that is not sufficient. We must be convinced of the significance of that awareness."

"Awareness," says Eddington. "Know thyself," says Socrates. "I see in my body the war of the members," says Paul. He did not think he would accomplish anything at all in his writings unless in some way, he induced that state. That is what he is trying to do. And that is why he used a method which, we may say, to the Jews is a stumbling block, to the Greeks foolishness. It can only be understood in one way, by entering in. It is like Paul's faith in Christ, it has to be lived from the inside; and that life is the death of the old life.

1 PtS-32 has 'it'.

2 PtS-32 has 'bringing'.

3 PtS-32 has 'that'.